An Experiment in Accelerometers, the Raspberry Pi, and Web Technology

Once a quarter my place of work grants our teams a ‘day of autonomy’ to work on any projects we see fit to grow our knowledge and development skill set. For ...

With the last post covering a brief overview of the project as a whole, I want to start discussing some of the more detailed subject matter surrounding the NES, starting with the CPU.

The NES CPU is based on the widly used 6502 microprocessor (as seen in the Apple II and Commodore 64), manufactured by Ricoh as the 2A03 and 2A07 microprocessor to accomodate for NTSC and PAL television systems, respectfully. The NTSC and PAL formats exist because analog television systems around the globe hold different standards for color encoding and refresh rate based on their region - at the time, many western countries used NTSC while most eastern countries adhered to PAL.

In order for the NES to accommodate these differing standards, two variations of the CPU had to be manufactured, but aside from these modifications the processors are otherwise identical. The CPU runs at a 1.79 MHz on the NTSC variant, and 1.66 MHz on the PAL variant, and houses 2KB of internal RAM. In addition, the CPU also handles processing for audio and controller I/O.

So how does the CPU start working with our games?

The CPU is in charge of translating compiled assemby code into actionable instructions based on the 6502’s instruction set. Once a ROM is loaded, the emulator initializes the program by determining the ‘starting point’, called the reset vector. Once the reset vector is determined the CPU reads in and processes the subsequent instructions which make up the mechanics of the game. One of the most laborious tasks in coming up with an emulator is transforming these instructions (also referred to as ‘opcodes’ in their compiled, byte-represented form) into their respective software-based implementations. The 6502 contains instructions for up to 256 unique opcodes, but of these 256 opcodes only 151 are offically supported.

If a ROM file is opened in a text editor, the opcodes are represented in 16, 2-byte segments, looking something like this:

78d8 a900 8d00 20a2 ff9a ad02 2029 80f0

f9ad 0220 2980 f0f9 09ff 8d00 808d 00a0

“Opcodes produced from compiled source code.”

Depending on the opcode being read in, these segments are interpreted differently. For instance, some opcodes may act implicitly (meaning that it executes on its own, without an operand), while others may require an operand ranging from 8 to 16 bits. Some opcodes also support multiple addressing modes, which add utility and allow them to be used in different ways.

If we take the first line of opcodes above and regroup them based on their addressing mode, their execution would look like this:

78 - d8 - a900 - 8d0020 - a2ff - 9a - ad0220 - 2980 (the first line of opcodes, regrouped based on their addressing mode)

1.) 78 -> SEI - Set Interrupt Disable (2 cycles)

2.) d8 -> CLD - Clear Decimal Mode (2 cycles)

3.) a9 00 -> LDA - Load Accumulator (value $00; 2 cycles)

4.) 8d 0020 -> STA - Store Accumulator (in address space $2000; 4 cycles)

5.) a2 ff -> LDX - Load X Register (value $FF; 2 cycles)

6.) 9a -> TXS - Transfer X to Stack Pointer (2 cycles)

7.) ad 0220 -> LDA - Load Accumulator (in address space $2002; 4 cycles)

8.) 29 80 -> AND - Logical AND (value $80; 2 cycles)

And so on - a standard ROM contains hundreds of opcode sequences.

A 6502 disassembler such as dcc6502 can help in manually breaking down and analyzing these opcode sequences to understand them a bit better.

You’ll notice that ‘cycles’ are called out in this example as well. Keeping track of CPU cycle counts becomes directly relevant during synchronization with the PPU (which I plan on discussing in a future post). For now it’s worth calling out that the PPU operates at 3 times the frquency of the CPU, so managing the timing between the two becomes crucial.

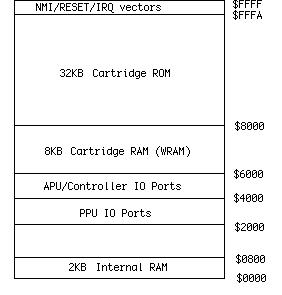

Since we’re on the subject of discussing how the CPU operates, I want to also address on some of the core components of the CPU memory map. While the CPU on the NES only utilizes 2KB of RAM, it turns out the 6502 can actually reference up to 64KB of memory.

So what is going on with the rest of that space? The remaining address space is used for PPU, APU, and I/O registers, as well as cartridge space for handling program ROM/RAM and mappers. Even then, segments of CPU and PPU address space are mirrored on the NES, presumably to save on the cost it would have otherwise taken to physically account for the unused address space outside of what was designated. A visual representation of how this address space is allocated looks something like this (credit to NintendoAge):

“A visual representation of NES CPU address space.”

“A visual representation of NES CPU address space.”

A well documented breakdown of how this address space is mapped can be found at the nesdev Wiki.

The CPU is highly intricate, and this post only scratches the surface. Fortunally, the nesdev Wiki covers all of these intricacies in painstaking detail.

Next up I plan on discussing how the CPU and PPU work together to display graphics on the screen.

kNES can be found on my GitHub page. This emulator is very much still in its infancy and published primarily to get the ball rolling on documentation and community support.

Once a quarter my place of work grants our teams a ‘day of autonomy’ to work on any projects we see fit to grow our knowledge and development skill set. For ...

With the last post covering a brief overview of the project as a whole, I want to start discussing some of the more detailed subject matter surrounding the N...

Writing an NES emulator has been a long time interest of mine, primarily because the subject of software emulation is fascinating. I’ve spent my fair share o...

It’s only been a few days since the last update, but I’ve decided to go ahead and comment on the overall status of this project and where I see it heading.

Wow, I can’t believe it’s already been over two weeks since the Game Off kicked off. This year’s theme is ‘Hybrid’.

Next month marks GitHub’s fifth annual Game Off, where participants spend one month creating games based on a theme that GitHub provides once the contest beg...

NES emulation has been done again and again for decades, yet seemly every year there is a new take on this monumental task using new languages, frameworks, a...